Peeling Away a Cause of Food Loss

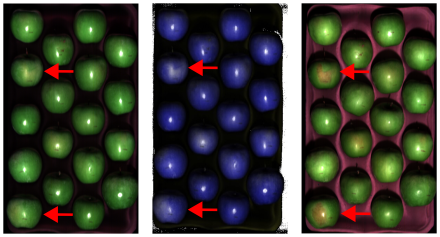

Granny Smith apples at-harvest (left), at harvest hyperspectral image pseudocolored with lighter blue to white regions indicating sunscald risk (center), and sunscald outcome after 6 months cold storage with symptoms developing beginning at 4 months (right). Red arrows point to at risk regions and the actual outcome.

Apples may be famous for keeping doctors away, but sometimes they suffer from ailments of their own. Sunscald is one such disorder, in which heat and light from the sun damage the outer layer of a fruit. The condition isn’t apparent at harvest, but appears weeks or months later, as the fruit moves through the cold storage chain and the peel begins to turn black. While affected apples are still edible, consumers don’t buy them because of their appearance, resulting in sizable annual losses to apple producers as well as food loss, a significant problem in the food system.

Working with colleagues at Washington State University, David Rudell, a research plant physiologist at the ARS Physiology and Pathology of Tree Fruits Research unit in Wenatchee, WA, has developed a novel technique to avoid the problem. The group has begun to use hyperspectral imaging to determine at the time of harvest which apples are at risk of developing sunscald. The imaging consists of scanning the fruit with sensors that can detect electromagnetic signatures associated with levels of natural chemicals that indicate portions of the peel more likely to develop the condition. To date, the technique has proven 95% accurate in identifying the scalded apples at harvest, well before any damage is visible to the human eye.

By identifying and removing the sunscalded apples from the rest of the harvest, producers can market them before the discoloration sets in, avoiding food loss and missed revenues. The researchers expect that their technology could be smoothly integrated into existing sorting lines in fields or at commercial facilities, reducing any cost associated with adopting it. In adding it to producers’ tools, they would be taking a significant step forward in the use of imaging in their industry.

“Hyperspectral imaging is not new in sorting, but what we’re doing differently here is we’re actually predicting something that hasn’t happened yet,” said Rudell. “We’re looking for chemical changes that indicate risk for disorders. It’s translational biology really,” he added, referring to the transformation of research findings into practical tools that U.S. apple and pear producers can use in daily operations. “That’s the big thing here: we’re sorting by something that you can’t see, so there’s that magic aspect there. You can’t see it and we’re mitigating that risk ahead of time.”

The value of that advanced knowledge is only likely to grow, as the increasing heat and drought of climate change raise the risk of sunscald. Over time, the researchers anticipate their technology could be used to predict other types of defects in fruit, too, saving farmers and consumers alike from additional food loss, and bringing a bit more stability to the supply of a cherished popular fruit. - By Kathryn Markham, ARS Office of Communications